Now that we have the book in our hands, it's time to figure out what to do with it, how to consult it, and how to best take advantage of its teachings. Since traversopractice.net is dedicated to the traverso, let's imagine that flutists look to Quantz's "Versuch" to see what it must tell us, starting with matters related to our instrument.

Which edition

First, we'll decide which edition to work with, which will previously be conditioned by the language. My first advice is that, in all cases, we should have access to the facsimile of the first editions from 1752, in German or French, not only for its terminological importance but also to have the musical examples in the original format.

As stated, Quantz published the "Versuch" almost simultaneously in two versions, one in German and the other in French (J. Fr. Voss, Berlin, 1752). The German version had two subsequent editions (Korn, Breslau, 1780 and 1789). They are thus two physically different books with the same structure but different pagination: the German edition totals 379 pages, while the French reaches 390.

Today, we can access facsimiles in different editions and formats. In addition to the downloadable versions on the IMSLP website, there are also German editions by Hans-Peter Schmitz (Bärenreiter, Kassel/Basel, 1953) and Barthold Kuijken (Bärenreiter, Wiesbaden, 1988), and the French by Pierre Séchet (Zurfluh, Paris, 1975, 8th ed, Ed. Robert Martin, 2011).

The interest that the "Versuch" aroused shortly after its publication is also evidenced by the Dutch version by Jacob Wilhelm Lustig (Olofsen, Amsterdam, 1754) and an anonymous one in English (Welcker, London, ca. 1775).

First, we'll decide which edition to work with, which will previously be conditioned by the language. My first advice is that, in all cases, we should have access to the facsimile of the first editions from 1752, in German or French, not only for its terminological importance but also to have the musical examples in the original format.

As stated, Quantz published the "Versuch" almost simultaneously in two versions, one in German and the other in French (J. Fr. Voss, Berlin, 1752). The German version had two subsequent editions (Korn, Breslau, 1780 and 1789). They are thus two physically different books with the same structure but different pagination: the German edition totals 379 pages, while the French reaches 390.

Today, we can access facsimiles in different editions and formats. In addition to the downloadable versions on the IMSLP website, there are also German editions by Hans-Peter Schmitz (Bärenreiter, Kassel/Basel, 1953) and Barthold Kuijken (Bärenreiter, Wiesbaden, 1988), and the French by Pierre Séchet (Zurfluh, Paris, 1975, 8th ed, Ed. Robert Martin, 2011).

The interest that the "Versuch" aroused shortly after its publication is also evidenced by the Dutch version by Jacob Wilhelm Lustig (Olofsen, Amsterdam, 1754) and an anonymous one in English (Welcker, London, ca. 1775).

|

Regarding modern translations, we have already highlighted the excellent English edition by Edward R. Reilly (On Playing the Flute, London, Faber and Faber Ltd., 1996, 2nd ed. 1985), which constituted the modern rediscovery of Quantz and remains an indispensable reference edition today. His masterful Introduction and critical apparatus remain an essential tool.

|

|

The Spanish-speaking reader has at least two translations: my own critical edition commented with a biographical reconstruction contained in my doctoral thesis "Johann Joachim Quantz y su aportación a la cultura musical del siglo XVIII", University of Murcia, 2015, available online, and the translation by Alfonso Sebastián Alegre published by Dairea in the same year.

|

|

The Italian reader can choose between the edition by Luca Ripanti (Rugginenti, Milan, 2nd ed. 2004), which includes the 1754 Autobiography, and the two editions by Sergio Balestracci (Libreria musicale italiana, Lucca, 1992) and Lucamaria Grassi (Turris, Cremona, 1992). These last are based on an anonymous translation commissioned by Giovanni Battista Martini on the copy that Quantz had sent him (ms. preserved in the Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale of Bologna). In Italian also, it would be necessary to mention the interesting "Saggio per ben suonare il flauto traverso" by Antonio Lorenzoni (Vicenza, 1779, facsimile ed. Forni, Bologna, 1969), which contains extensive translated extracts from the "Versuch".

|

|

Reading Quantz...

Quantz's style is quite plain and usually focuses on the practical. He often uses the "rules" approach typical of didactic literature: presenting a practical case and explaining the rule that serves to resolve it. Sometimes he falls into excessive pedantry and not a few redundancies. As is known, repetita iuvant, the patient teacher's voice has not changed much from yesterday to today! However, the text is easily accessible to a modern reader. In the originals, the only possible reading difficulty could be the Fraktur typeface of the German version. Key words (many of them items from the Register at the end of the book) are highlighted with a larger font size (or in small caps, bold or italic, depending on the edition). The text is organized into numbered paragraphs, sometimes grouped into sections. This allows us to refer to specific content regardless of the edition. For example, in any of the editions or translations, Paragraph §8 of Chapter IV will always be the one that explains how to place the lips on the flute's mouthpiece. This way, we can also compare this instruction and the terminology used in any of the languages we are using. |

|

... and playing!

Many of the rules are accompanied by brief musical examples. This invites to take the flute and experiment. In the original editions these examples were grouped into 24 tables in a separate booklet. This was common in musical editions of the time due to the typographic technology used. The text of the book was printed with movable type, while the musical tables used copper plates. When the reader encountered a reference to a certain table, they would open the separate booklet to examine the musical example in question alongside the text. In modern editions, the musical examples are inserted directly into the text. Among the examples, two complete pieces stand out for its didactic value: a beautiful Adagio with detailed instructions for ornamentation (in the manner of the slow movements of Telemannn's Methodical Sonatas) and another Affettuoso di molto with extraordinarily precise dynamic indications. |

Start at the end

The book has the following broad structure:

- Dedication and Preface

- Introduction: Of the Qualities Required of Those Who Would Dedicate Themselves to Music

- 18 Chapters

- Index (Register) of the Most Important Matters.

The book has the following broad structure:

- Dedication and Preface

- Introduction: Of the Qualities Required of Those Who Would Dedicate Themselves to Music

- 18 Chapters

- Index (Register) of the Most Important Matters.

|

For a moment, let's skip the entire body of the book and move towards the end. Here we find what I consider an essential tool for a first contact and for consultation, which is often overlooked. It's the Register (Table alphabetique), the listing of the main subjects that closes the book. It's the analytical index of the book compiled by Quantz himself, which probably reflects the list of arguments the author elaborated during the preparation phase of the work. The Register lists the arguments in alphabetical order, indicates their location in the body of the book (which chapter and which paragraph), and classifies many of the items into more general themes. In modern editions and translations, the Register is presented in various ways. For example, Reilly integrates it into his index of arguments to include his critical apparatus and uses the page numbers of his edition as references. Other editors simply translate Quantz's Register. In my doctoral thesis, I opted to organize it into a comparative table between the original German and French languages and the Spanish translation.

|

A treatise of treatises

Indeed, the "Versuch" is a collection of essays on various subjects, condensed around the "improvement of taste" claimed in the German title and well explained in the Preface. Quantz arranges his content in a concentric ascending journey, from particular (the flute) towards the general (taste). In each turn, it is possible to glimpse topics treated previously or still to be addressed, allowing us also to enter through different doors and at different levels. A musicologist might be more interested in the last chapter, an orchestra conductor in the chapter on accompaniment, and an instrumentalist in those dedicated to ornamentation.

Indeed, the "Versuch" is a collection of essays on various subjects, condensed around the "improvement of taste" claimed in the German title and well explained in the Preface. Quantz arranges his content in a concentric ascending journey, from particular (the flute) towards the general (taste). In each turn, it is possible to glimpse topics treated previously or still to be addressed, allowing us also to enter through different doors and at different levels. A musicologist might be more interested in the last chapter, an orchestra conductor in the chapter on accompaniment, and an instrumentalist in those dedicated to ornamentation.

|

As is common with "broad spectrum" treatises, the "Versuch" draws from many sources. It is the first flute treatise in German and the third chronologically, following the two in French by Jacques Hotteterre (1707) and Michel Corrette (circa 1735). Most subsequent treatises (Mahaut, Lorenzoni, Gunn, up to Tromlitz) would demonstrate the referential role assumed by Quantz's "Versuch". To properly place Quantz in his context, it is particularly important to know these sources and to establish parallels with Quantz's teachings.

|

For example, regarding articulation, flutists find Quantz's adherence to the early French flute school striking, more specifically to that of Hotteterre, linked to the "classical" style of Lully, than to that of Corrette, more inclined towards the modern Italian style. In the next article, we will see how to approach this, and other questions raised by the study of Quantz.

However, the breadth of topics covered in the "Versuch" allows for the recognition of many other sources and influences, besides those strictly related to the flute, such as Gasparini, Tosi, Tartini, Mattheson, Telemann, Gottsched, Marpurg, Majer, Scheibe, and others.

All this without forgetting that Quantz's is the first in the extraordinary series of analogous musical treatises, like the one by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach for the keyboard (1753-1762), Leopold Mozart on the violin (1756), or Friedrich Agricola on singing (1757, expanded translation of Tosi's from 1723). Among them, Quantz's arguably offers the most panoramic view on the musical world of his time.

However, the breadth of topics covered in the "Versuch" allows for the recognition of many other sources and influences, besides those strictly related to the flute, such as Gasparini, Tosi, Tartini, Mattheson, Telemann, Gottsched, Marpurg, Majer, Scheibe, and others.

All this without forgetting that Quantz's is the first in the extraordinary series of analogous musical treatises, like the one by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach for the keyboard (1753-1762), Leopold Mozart on the violin (1756), or Friedrich Agricola on singing (1757, expanded translation of Tosi's from 1723). Among them, Quantz's arguably offers the most panoramic view on the musical world of his time.

A flutist's guide to Quantz's Versuch

Now, let's see how we can approach such a comprehensive work without fear. It would be a mistake to start reading it linearly, as if it were a novel or a "specialized essay." Some topics are concentrated in certain places, but more often, they are scattered throughout the text or repeated differently depending on the context. For example, legato might appear as a "rule" for flute articulation, but also during the explanation of the appoggiatura within ornamentation, in the section dedicated to the violin within accompaniment, or even when Quantz expounds his ideas on "cantabile" or the style of opera singing. In this sense, turning to the Register first can help us identify themes in advance and be prepared when we encounter them.

Now, let's see how we can approach such a comprehensive work without fear. It would be a mistake to start reading it linearly, as if it were a novel or a "specialized essay." Some topics are concentrated in certain places, but more often, they are scattered throughout the text or repeated differently depending on the context. For example, legato might appear as a "rule" for flute articulation, but also during the explanation of the appoggiatura within ornamentation, in the section dedicated to the violin within accompaniment, or even when Quantz expounds his ideas on "cantabile" or the style of opera singing. In this sense, turning to the Register first can help us identify themes in advance and be prepared when we encounter them.

|

The "Versuch" aims to cover all phases of musical learning, from the initial motivation of the beginner to the ultimate definition of the professional musician. Some parts of the book may be difficult in a first reading not because they are, but because they deal with matters that the novice reader still does not know. This reader will have to "keep the book warm", experiment with the "rules," and return periodically to the text in search of new revelations.

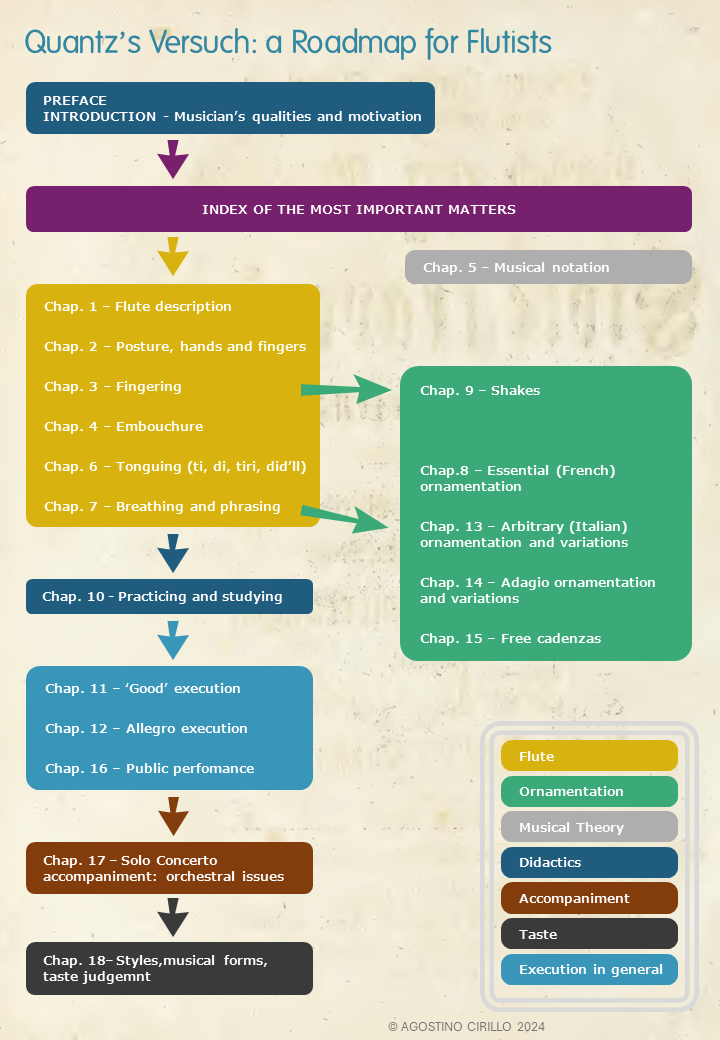

In summary, there are many ways to approach the "Versuch." The simple linear reading may be the least effective. Depending on each reader's interests, one can even enter the book from the last chapter. In the case of flutists, especially if they are students or beginners, my proposal is to follow the scheme in the hereby graphics. |

|

Delving into the content

Let's first focus on two graphic details that, far from being merely decorative, also have a lot to do with Quantz's biography. The engraving that opens the Introduction is titled "Principium Musicum" and depicts the legend of Pythagoras, caught while hearing hammers striking an anvil in a forge and discovering the acoustic phenomenon of harmonics, conceiving the harmonic triad. The triad is represented on a shield, as a badge of nobility for the musician's profession. This is a clear reference to the blacksmith's shop where Quantz was born and to which he was destined if his father had not left him an orphan. Significantly, this anecdote is narrated discreetly in the Introduction of the Versuch and more explicitly in Burney's interview, towards the end of his life. |

|

The other engraving is at the end of the book. Under the title "Executio Anima Compositionis" (execution is the soul of the composition). It is a real musical scene, framed by rich decoration made of festoons and musical instruments, where a flute crossed with an oboe stands out (as we know, two significant instruments for Quantz). Around a harpsichord, there are seven musicians. In the foreground, the soloists are observed: a singer, standing, holding a score in his hands, and a flautist. With their backs to the observer are a harpsichordist and a cellist, and in the background two violinists and a standing violist. It could very well be a perspective of the Konzertzimmer at Sanssouci, and it is not difficult to identify the famous private concert of Frederick, at a moment when the musicians are performing an aria for voice, obbligato flute, and strings in real parts.

|

|

The dedication to Frederick is concise and to the point, clarifying who sponsored its production. It also makes clear that Quantz did not need to grovel and beg his patrons, as was customary for musicians publishing their works.

|

|

The Preface briefly explains the book's purpose, the "improvement of taste," and declares it is directed both at professionals and amateurs. This is an important warning, as usually treatises on instruments were aimed at dilettantes. Quantz insists on the need to form good judgment in those aspiring to be musicians, even if dedicated to accompaniment, which he considers an activity as committed and relevant as that of the solo virtuoso. Notice how, right from the first paragraphs of the Preface, the book's most relevant concepts are threaded together: method, flute, taste, musical practice, singing, instruments, good execution, soloist, accompaniment, judgment, musician, composition, musical profession, amateurs.

|

|

The Introduction, titled "Of the Qualities Required to Dedicate Oneself to Music," will be especially stimulating for those particularly concerned with musical pedagogy, whether as students or teachers. It's organized in paragraphs like the rest of the chapters, but the author has decided to elevate it to the most prominent place. Effectively, along with the final Chapter XVIII, the Introduction frames the book from beginning to end. Drawing on authority gained in real life and based on his experience, Quantz reviews everything that dedicating oneself to music entails: early recognition of natural inclination, smart use of talent, intelligent and diligent study, the effectiveness of didactics, profitable learning, the better or worse fortunes of a career, different professional categories, choosing a specialty (including that of composer), the place of music among the arts, and even the moral attitude of the musician. It's almost unique in the musical literature of the era and, in many aspects, surprisingly relevant even today.

|

|

Flute and its technique will be the first step for us to seek. Fortunately, this is circumscribed in the first chapters of the book. It's worth noting that this set of information barely reaches 15% of the total book. What would then be the "Quantz flute treatise" in a strict sense occupies no more than 50 pages, a length not very different from the treatises on flute that precede it, those of Hotteterre (1707) and Corrette (circa 1735). In fact, the arrangement of the arguments is similar in the three treatises.

We'll notice that Chapters VI, on articulation, and VII, on breathing, also deal with general flute execution issues, such as phrasing and tempo. In a subsequent phase, we would explore the chapters on execution, starting with Chapter IX on trills, which complements the information on flute fingering presented in Chapter III. |

|

Regarding ornamentation, I would start with what Quantz calls "essential," namely appoggiaturas, mordents, and trills (Chapters VIII and IX), where the French influence from his training period in Dresden is evident. Quantz insists more than once on the importance of studying instrumental music in the French style carefully to achieve crisp execution and refined technique.

However, one of the strengths of the "Versuch" is its extraordinary analysis of "arbitrary" ornamentation, that is, rhythmic-melodic variation based on the Italian tradition of "diminution." At Quantz's time, the ability to improvise ornamentations distinguished the professional virtuoso musician from the orchestra musician (ripienist) or the mere amateur, who needed a written score to make music. It's surprising to think how a large part of the Baroque music repertoire has come down to us in printed editions generally intended for an amateur audience. Without phonographic recordings, it's difficult to know how the great virtuosos really played in an era where improvised variation was the focus of audience attention. We must rely on the relatively scarce written documents, the technique of the instrument, stylistic constraints, and our imagination and common sense. Which is no small thing! Quantz dedicates Chapters 13 and 15 to this topic. The musical examples accompanying them are very useful for those who wish to start in free ornamentation, both on the flute and on other instruments. Quantz goes beyond the simple formal elaboration of the ornament, insisting on its expressive realization, as shown in the masterful ornamented and commented Adagio that closes the brilliant Chapter 14. How should one work with this material? My advice is to systematically approach the study of these tables, analyze them melodically note by note over each proposed chord (e.g., using numbers, as done in jazz), reconstruct them in different keys, memorize them, and apply them in "real world" sonatas, first as presented by Quantz, and then by adding first essential ornaments and then further elaborations in the same style. |

|

Dynamics and tempo are topics that Quantz is perhaps the first to systematically address, both in terms of flute technique and its use for expressive performance. For example, his instructions on the energy of each dissonance and its realization by the accompanying harpsichordist (Section VII of Chapter XVII) should obviously concern us flutists as well. The Affettuoso di molto that closes this section explicitly shows the various possible nuances note by note and represents a fantastic exercise in phrasing and control of sound and intonation, to which only an ornamentation in the manner of Quantz would need to be added.

|

|

The extensive Chapter XVII, which occupies almost a third of the entire book, analyzes accompaniment in detail for each type of instrument, from strings to keyboards. Here again, the stylistic framework of reference is that of the Italian-style sonata and solo concerto, although there are also touches on theater music and even church music.

|

|

Finally, in Chapter XVIII, also very extensive, Quantz elaborates a detailed panorama of the musical world of his time. His aim is to define a concept of "taste" that allows appreciating what is truly good in music, both for the professional and for the student and amateur, as well as for the mere listener. For this purpose, he formulates quality parameters for each form and genre, examines the virtues and defects of the French and Italian national styles, and advocates for a "mixed" style like the one that has emerged in German territory.

|

From experience to practice

Knowing Quantz's biography, it's possible to see how the "Versuch" reflects his experiences as a Stadtpfeifer and later court musician, especially in Dresden. In practical terms, we have his "rules" of performance, affecting not just the flute but also other instruments in the accompaniment, and all possible issues related to teaching and performance (sound, acoustics, tuning and temperament, articulation, tempo, style, expression, etc.). In the theoretical realm, especially in the Introduction and in Chapter XVIII, ideological and aesthetic themes are concentrated. I avoid the term "theoretical" because Quantz's approach is always practical and concrete, referring to real cases.

Especially in the first chapters about the flute, the attentive reader will encounter certain discrepancies with the practice they know of the instrument. It's normal for doubts and questions to arise, starting with the fingering, since it's evident that the flute Quantz talks about is his model with two keys and not the "normal" one-key flute.

Knowing Quantz's biography, it's possible to see how the "Versuch" reflects his experiences as a Stadtpfeifer and later court musician, especially in Dresden. In practical terms, we have his "rules" of performance, affecting not just the flute but also other instruments in the accompaniment, and all possible issues related to teaching and performance (sound, acoustics, tuning and temperament, articulation, tempo, style, expression, etc.). In the theoretical realm, especially in the Introduction and in Chapter XVIII, ideological and aesthetic themes are concentrated. I avoid the term "theoretical" because Quantz's approach is always practical and concrete, referring to real cases.

Especially in the first chapters about the flute, the attentive reader will encounter certain discrepancies with the practice they know of the instrument. It's normal for doubts and questions to arise, starting with the fingering, since it's evident that the flute Quantz talks about is his model with two keys and not the "normal" one-key flute.

We will discuss these and other questions in detail in the following article.

© Agostino Cirillo 2024