The Flute of Quantz

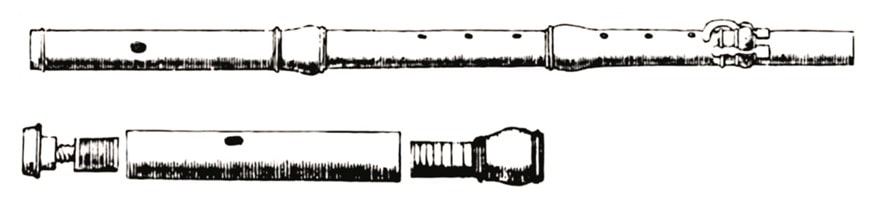

The flute that Quantz discusses in the "Versuch" is not exactly the one-keyed traverso we commonly use today, but rather the improved model that he himself had been developing.

The flute that Quantz discusses in the "Versuch" is not exactly the one-keyed traverso we commonly use today, but rather the improved model that he himself had been developing.

Its features are described in a French article for the Diderot’s Encyclopédie, signed in 1777 by Frédéric de Castillon, probably one of his students in Berlin:

- A second, longer key for the right pinky, covering a hole (smaller than the one for the short key) with the purpose of improving (i.e. lowering) the sharp notes.

- Very low pitch, i.e. greater length, diameter, and thickness of the wood, generating that “voll, dick und männlich” (full, round, and masculine) timbre he considers ideal for the instrument.

- Adjustable screw for the cork stopper that allows vary the pitch according to the corps de rechange used.

- Telescopic joint in head joint, for fine pitch adjustments without changing the central body.

- A finger holes distance that allows for a just natural F (not higher, like in most flutes), very much in line with the abundance of flat keys in the Dresden and Berlin repertoire and with the low pitch of F# as the third of D, the flute’s home key.

|

Another particularly controversial feature that Quantz vaguely discusses in the "Versuch" (Chap. IV, §5) is the tuning of open octaves instead of pure ones, so that they can be tuned using the technique he proposes of opening the embouchure with the lower lip for the lower notes and closing it for the higher ones. According to Quantz, this facilitates the production of powerful bass and soft, delicate trebles, a type of execution surely suited for the large leaps between registers in Telemann's Fantasias or Braun's Solos, for example:

|

As Mary Oleskiewicz has pointed out (see her referential The Flutes of Quantz: Their Construction and Performing Practice, The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 53, Apr. 2000, pp. 201-220), this feature is usually not present in current copies of Quantz flutes, which tend to limit themselves to the presence of the second key and the internal measurements of the original model chosen. Even regarding the pitch, the current simplification by semitones that crystallizes around A=440Hz ("modern" pitch), 415Hz (a semitone lower, "baroque" pitch), and 392Hz (a whole tone lower, "French" pitch) has led to many Quantz flute copies at familiar 415Hz, when among the original remaining Quantz flutes the one with the shorter body (i.e., well above average) only reaches up to 410Hz. Perhaps the standard pitch most in line with Quantz's ideas is 392Hz, which brings the Quantz flute closer to the old three-parts French models like Hotteterre.

I know no current flutist who uses Quantz's particular embouchure technique for register jumps nor a Quantz flute that combines all the features mentioned. While it's true that the long key can help tune some sharp notes in slow pieces, it's also true that any note can (must) be tuned with maximum precision on the ordinary one-key flute, using air control, jaw mobility and flute axis rotation with fine embouchure management or employing alternative fingerings (of which, the second key allows indeed more to experiment with).

Among the dozen instruments made by Quantz that are preserved today, not all these features are seen together, suggesting an evolutionary and experimental process that began with the idea of the second key conceived in Paris in 1726, namely with the primary purpose of obtaining "just" temperament. We also know that each of the flutes Quantz made for Frederick the Great met his specific demands at the time of request.

This also explains how many of the Quantz's ideas about pitch, tuning, fingering, and the flute's timbre were already obsolete in 1750 decade and were quickly discarded thereafter. But this should not worry us: the philosophy of period music making is exactly that of reviving through contemporary sources the instruments and the techniques that at some point were considered obsolete!

Among the dozen instruments made by Quantz that are preserved today, not all these features are seen together, suggesting an evolutionary and experimental process that began with the idea of the second key conceived in Paris in 1726, namely with the primary purpose of obtaining "just" temperament. We also know that each of the flutes Quantz made for Frederick the Great met his specific demands at the time of request.

This also explains how many of the Quantz's ideas about pitch, tuning, fingering, and the flute's timbre were already obsolete in 1750 decade and were quickly discarded thereafter. But this should not worry us: the philosophy of period music making is exactly that of reviving through contemporary sources the instruments and the techniques that at some point were considered obsolete!

The Well-Tempered Flutist

Whether using a common one-keyed traverso or a properly made Quantz flute with two keys, what truly matters to us is understanding and applying the concept of "just" tuning that Quantz promotes and its relationship with expression and affective musical contents. This is a type of temperament for variable-pitch, or melodic instruments (non-keyed) documented in numerous sources from the first half of the century, like Tosi (translated into German by Agricola) for singing or L. Mozart and Preuller for the violin.

Whether using a common one-keyed traverso or a properly made Quantz flute with two keys, what truly matters to us is understanding and applying the concept of "just" tuning that Quantz promotes and its relationship with expression and affective musical contents. This is a type of temperament for variable-pitch, or melodic instruments (non-keyed) documented in numerous sources from the first half of the century, like Tosi (translated into German by Agricola) for singing or L. Mozart and Preuller for the violin.

|

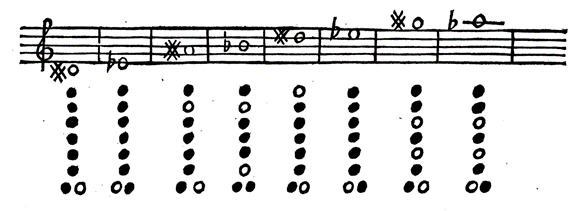

In very simple terms, in this temperament, a whole tone is divided into nine micro-intervals, named commas, where the two asymmetric major and minor semitones are found. The major semitone is the minor second interval, e.g., between C and D flat, while the minor semitone is the distance between a note and its ascending chromatic alteration (e.g., between C and C sharp), according to the following scheme:

|

|

This temperament shows that D flat does not coincide with C sharp (as in the "modern" equal temperament), but is one comma (i.e., a ninth of a tone) above C sharp. Considering that the difference between a pure third and a tempered third is about 12 cents, this enharmonic comma of Quantz's is almost twice as large, a difference very noticeable by ear. In fact, if we remove the two keys from a Quantz flute, the size difference between the two holes is immediately evident: the one for the long key (for the sharps) is considerably smaller than that for the normal short key, which means that the notes using it will be lower without needing to adjust the embouchure.

|

Ideally, the tuning of Quantz should be applied across all music related to some type of Meantone or Well-tempered system, contemporary or better preceding Quantz's Versuch, and even afterwards, with more exceptions up to the classical period.

In any case, his recommendations fall within the more general objective that the flute be on par with singing and can expressively draw and shape the melody, where tuning is a component closely linked to timbre. One of the best flute teachings I have received in this regard is that tuning is not just 'tuning' but first listening and then focusing on the timbres and colors, the self and the other. And it was imparted to me by a singing teacher.

In any case, his recommendations fall within the more general objective that the flute be on par with singing and can expressively draw and shape the melody, where tuning is a component closely linked to timbre. One of the best flute teachings I have received in this regard is that tuning is not just 'tuning' but first listening and then focusing on the timbres and colors, the self and the other. And it was imparted to me by a singing teacher.

|

Clean ears...

To achieve this, it's not enough to merely use the Quantz long key or apply a certain fingering; it's necessary to train the ear to recognize the just pitches of each note according to its vertical harmonic context and to reproduce these differences with the flute in each situation. Quantz's concept of "sharps-lower-than-flats" points towards a harmonic system where the thirds of triads (and their inversion, the sixths) are pure or nearly so. In a major key, this particularly affects the third and seventh degrees of the scale (i.e., the leading tone of the key). For instance, in D major, the F# should be lowered as the third over the tonic while the C# should be lowered as the third of the dominant. This latter goes directly against the so-called "expressive" modern tuning, where leading tones are often raised to enhance their penchant to the tonic. Since the 19th century, this concept has been firmly embedded in instrumental pedagogy and our hearing, along with the adoption of Equal temperament with its sharp thirds. Weather the technical means that Quantz proposes are not available or they are not the most suitable, his concept of tuning should be highly recommendable for flutists, and, in general, for singers and melodic instrumentalists playing Baroque repertoire. This implies opening mind and reprogramming our "modern" ear to vary the pitch of each note in real time according to the harmony's demands. The adjustment affects not only the altered notes but also the naturals ones, implying, for example, that we must sometimes change the pitch of a natural D by adjusting inwards or towards the embouchure whether it is the tonic of a D chord (pure unison or octave to the root), the major third of Bb major (lower), the minor third of B minor (higher) or the fifth of G major (just slightly higher). The timbral quality produced is noticeable and pleasing to the ear, as consonances sound like that, i.e. real consonances, harmonic progressions gain meaning, and the ensemble texture gets enriched by the so-called virtual "third sounds", one octave lower for pure fifths and two octaves lower for pure thirds. |

It's truly rewarding to listen string ensembles to play Muffat, Corelli, or Vivaldi music with these tuning criteria. Conversely, I find tedious to listen to the same music within a modern equal temperament tuning concept, even when well played with Baroque bows, gut strings and even "Baroque" poses. The difference is striking: timbre is dry, harmony is flat, discourse is idle as a great part of original intended musical consonance-dissonance dialectic is lost. This is a reason for trying to artificially compensate the lack of aural intensity playing too much stronger and too much faster. For a modern-trained violinist (who, on the other hand, can technically play almost any Baroque music at first sight), it's particularly challenging not only to play with gut strings, with a Baroque bow, without (or with a different type of) vibrato, but also to develop ear to place the finger in different spots for the same note and react to the harmony in real time, all while maintaining melodic intensity. But the difference is noticeable, and the serious work to achieve that result must be rewarded!

|

... and smart eyes

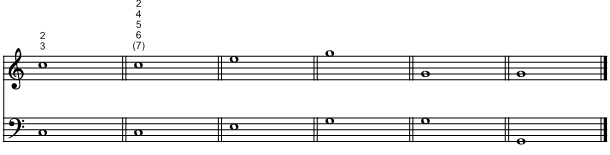

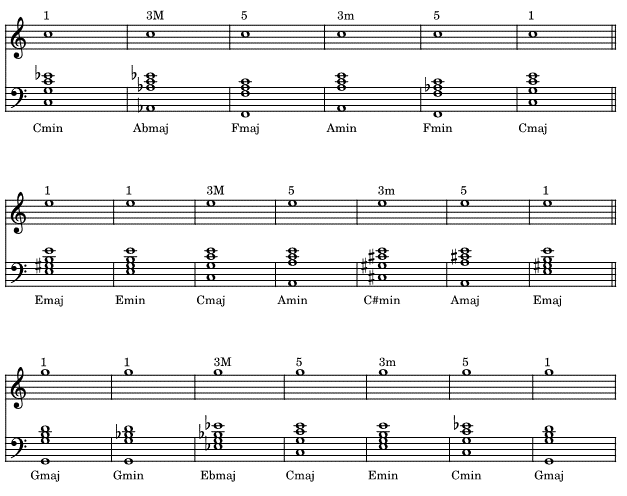

The first step to enter this fascinating issue is to build the habit to always analyze the melody we are going to play, how it is built, and elaborated onto the bass, and assess the interval that each note forms with the other voices, starting with the root of the chord it belongs to. We will do this in writing down numbers corresponding to the interval (as sometimes done in the analysis of solos in jazz music). Gradually, we will observe how a new analytical view of the melody grows up internally, like a second nature, that allows us to read and place each note in its correct spot, in tuning, tension and color. As Quantz points out, the good intonation of the ensemble is a task for every single musician. Here's a little example of melodic analysis with a real-life fragment from Quantz himself. The number 1 is used here for the root of the chord, but you can meaningly substitute it for an 8 (if it's an octave up) or simply for a R[oot] letter. It's important that the number shows the interval with the fundamental bass, no matter whatever inversion the actual bass is sounding (that is a sound color itself indeed!). As we progress on this practice, the first candidates to receive our tuning/timbre "intensive care" will be the long consonant notes in slow movements, on strong beats, at harmony changes, or at the end of cadences, i.e. whenever the harmonic quality is best appreciated by the listener. Starting to experiment with equal instruments repertoire is easiest. As Quantz wisely suggests, the wonderful flute duets by Telemann or his own are very suitable for refining the ear and experimenting with pitch flexibility (and, obviously, more!). The following step is to transfer this experience to ensemble music with accompaniment instruments.

|

To play in tune...play out of tune!

We know that keyboards cannot vary the pitch of each note on the fly as the voice, violin or flute can, and for each of their keys, they must choose one fixed pitch. This is done by setting the keyboard in one temperament or another. They are nothing more than mathematical-empirically based systems designed to divide the octave into twelve half tones. If they are equal, we'll talking about Equal temperament; if they are unequal (some wider, others narrower), we are using one of the so-called historical temperaments, such as a Meantone, a Vallotti, a Werckmeister or a «Well-tempered”, etc. Each of them is often related to specific styles and periods.

I'd propose two practical experiments that serves as an introduction to develop a finer ear to Baroque tuning subtleties and a quicker response to resolve on the flute harmonic issues with other instruments. Quantz flute owners can also practice the second key and assess its real usefulness alternating with the normal one, especially in the last enharmonic experiment, that is based on the Quantz fingerings involved.

The experiments involve the collaboration of a (human) keyboard player or, in their absence, a recording of one. For the computer geeks, a sequencer or DAW with a decent keyboard sound can serve the purpose, recording series of notes, chords, and arpeggios to play along with the flute.

We know that keyboards cannot vary the pitch of each note on the fly as the voice, violin or flute can, and for each of their keys, they must choose one fixed pitch. This is done by setting the keyboard in one temperament or another. They are nothing more than mathematical-empirically based systems designed to divide the octave into twelve half tones. If they are equal, we'll talking about Equal temperament; if they are unequal (some wider, others narrower), we are using one of the so-called historical temperaments, such as a Meantone, a Vallotti, a Werckmeister or a «Well-tempered”, etc. Each of them is often related to specific styles and periods.

I'd propose two practical experiments that serves as an introduction to develop a finer ear to Baroque tuning subtleties and a quicker response to resolve on the flute harmonic issues with other instruments. Quantz flute owners can also practice the second key and assess its real usefulness alternating with the normal one, especially in the last enharmonic experiment, that is based on the Quantz fingerings involved.

The experiments involve the collaboration of a (human) keyboard player or, in their absence, a recording of one. For the computer geeks, a sequencer or DAW with a decent keyboard sound can serve the purpose, recording series of notes, chords, and arpeggios to play along with the flute.

This practice also tries to answer a typical question many of you might have in chamber or ensemble: "Ok, I want to play my sweetly sounding flute consonances… But what happens with the harpsichord? Must we exactly play the notes corresponding to its fixed temperament, or may we vary them following Quantz's vocal ideal concept?"

For this experiment, the specific temperament harpsichord is tuned in doesn't matter too much since the goal is to awaken the flutist's ability to correct their tuning within a harmonic context. Obviously, the room cleaning first: the harpsichord (even on a computer DAW this can be done) must be correctly tuned, for example, in a familiar Vallotti temperament at 415Hz.

By the way, learning to tune and temper a harpsichord is like vitamins for flutist (and your continuo player will love you!)

For this experiment, the specific temperament harpsichord is tuned in doesn't matter too much since the goal is to awaken the flutist's ability to correct their tuning within a harmonic context. Obviously, the room cleaning first: the harpsichord (even on a computer DAW this can be done) must be correctly tuned, for example, in a familiar Vallotti temperament at 415Hz.

By the way, learning to tune and temper a harpsichord is like vitamins for flutist (and your continuo player will love you!)

Experiment 1: find the starting point

Step 1

Let’s choose the C major triad. Tune the notes C', E'', and G' and G'' separately, seeking unison and pure octaves with each of the harpsichord notes. Experiment with embouchure rotation to keep focused timbre and to vary the pitch.

Step 1

Let’s choose the C major triad. Tune the notes C', E'', and G' and G'' separately, seeking unison and pure octaves with each of the harpsichord notes. Experiment with embouchure rotation to keep focused timbre and to vary the pitch.

You’ll need to test the pitch of some of your notes. This is due to the temperament of the harpsichord (for example, in Vallotti, both E and G are slightly lower than in equal temperament) and to the characteristics of the flute itself: on some flutes, G' might be a bit low, while E'' and G'' might be a bit high. For C', experiment with the fingering 2456(7), which is slightly higher and more open colored than 23.

The goal now is to carefully listen and "match" with the flute timbre the perceived timbre of the harpsichord as closely as possible, especially paying attention to the decaying string's resonance immediately after the pluck attack. Sound care is key: to focus on internal ear sensations many musicians keep eyes closed while tuning, and in old sources we find recommendations about studying in a dark room!

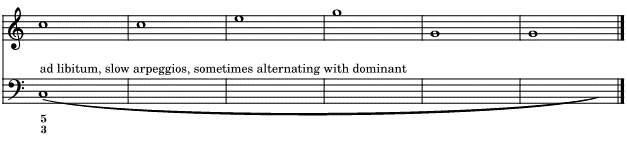

Once the unisons and octaves pitches/timbres are internally settled and memorized, the harpsichord will play the C major triad arpeggiating slowly, doubling the bass and varying the voicing to create a well-defined tonal sensation, akin to a prelude. It will be useful to sometimes alternate between C major, its dominant, G major or similar, and other grades and inversions to amplify harmonic stimulus.

The goal now is to carefully listen and "match" with the flute timbre the perceived timbre of the harpsichord as closely as possible, especially paying attention to the decaying string's resonance immediately after the pluck attack. Sound care is key: to focus on internal ear sensations many musicians keep eyes closed while tuning, and in old sources we find recommendations about studying in a dark room!

Once the unisons and octaves pitches/timbres are internally settled and memorized, the harpsichord will play the C major triad arpeggiating slowly, doubling the bass and varying the voicing to create a well-defined tonal sensation, akin to a prelude. It will be useful to sometimes alternate between C major, its dominant, G major or similar, and other grades and inversions to amplify harmonic stimulus.

Step 2

Sustain mezzo forte a good C', which, being the tonic of the triad, should seek absolute unison or pure octave with the bass. When achieved, experiment varying the intensity and exploring the dynamic range allowed by the fingering.

Shift to a sustained E'' over the harpsichord chord. Initially, the same E'' unison or octave must be repeated.

Now start to lower the E'' it very slowly and gradually. You will notice how this lower E'' seems to better settle into the harpsichord's harmony. This is because the ear gratefully appreciates the sensation of a pure major third interval, which is about 12 cents narrower than the equal tempered one.

The difference becomes clear if the flute maintains the newly found consonant E'' and the harpsichord interrupts the chord to play only its E note: the two E's are clearly different but within the chordal harmonic context the "new" low E from the flute sounds surprisingly more consonant than the higher one taken from the harpsichord.

Moreover, you get a range where you can choose the consonance grade of your third, within a pure third (stable and sweet) up to a modern equal temperament third (harsher and unstable).

Something similar happens with G, the fifth of the C major triad, with the sole difference that the G must be only slightly higher, much less different than the E, as a pure fifth is only 2 cents higher than a tempered one.

Sustain mezzo forte a good C', which, being the tonic of the triad, should seek absolute unison or pure octave with the bass. When achieved, experiment varying the intensity and exploring the dynamic range allowed by the fingering.

Shift to a sustained E'' over the harpsichord chord. Initially, the same E'' unison or octave must be repeated.

Now start to lower the E'' it very slowly and gradually. You will notice how this lower E'' seems to better settle into the harpsichord's harmony. This is because the ear gratefully appreciates the sensation of a pure major third interval, which is about 12 cents narrower than the equal tempered one.

The difference becomes clear if the flute maintains the newly found consonant E'' and the harpsichord interrupts the chord to play only its E note: the two E's are clearly different but within the chordal harmonic context the "new" low E from the flute sounds surprisingly more consonant than the higher one taken from the harpsichord.

Moreover, you get a range where you can choose the consonance grade of your third, within a pure third (stable and sweet) up to a modern equal temperament third (harsher and unstable).

Something similar happens with G, the fifth of the C major triad, with the sole difference that the G must be only slightly higher, much less different than the E, as a pure fifth is only 2 cents higher than a tempered one.

This experiment should be repeated with other intervals, like minor thirds (more open than the major thirds), major and minor sixths (opposite to their correspondant thirds), thirds as leading notes in dominant grades. Changing to other keys, you’ll notice the little distance shifts between the notes (which is what Quantz calls "proportion") and how they vary according to the underlying harmony.

It's important to awaken the ear to these sensations and to maintain them during the study of the repertoire. The custom to develop long consonant notes in small improvised preludes before playing a piece is related to this settling of the ear and fingers in the harmonic environment, whatever it is.

It's important to awaken the ear to these sensations and to maintain them during the study of the repertoire. The custom to develop long consonant notes in small improvised preludes before playing a piece is related to this settling of the ear and fingers in the harmonic environment, whatever it is.

Experiment 2: move your notes up and down

Now let’s approach an experience more like real life. Let’s help us now with melodic analysis numbers. They tell us about the interval over the root of the chord, named sometimes “fundamental bass” in antique sources. For the flute they indicate also the task involved:

Play and sustain one same note over different chords. Listen, look at the interval number and experiment rising and lowering the pitch by slow and slight embouchure and jaw moves. Search for best consonances, even with dynamics increasing and decreasing. Check your flute response. Experiment with pitch ranges and different fingerings.

Now let’s approach an experience more like real life. Let’s help us now with melodic analysis numbers. They tell us about the interval over the root of the chord, named sometimes “fundamental bass” in antique sources. For the flute they indicate also the task involved:

- 1 (or 8 or R) exact pure unison or octave.

- 3M: lower toward pure major third.

- 3m: rise toward pure minor third.

- 5: rise slightly toward pure fifth.

Play and sustain one same note over different chords. Listen, look at the interval number and experiment rising and lowering the pitch by slow and slight embouchure and jaw moves. Search for best consonances, even with dynamics increasing and decreasing. Check your flute response. Experiment with pitch ranges and different fingerings.

Step 2: enharmonic shifts

When we have got proficiency with the harmonic qualities of notes, let’s have fun with the weird and tricky side. With pairs of enharmonic notes we are in the most challenging of the Quantz territories: if you can, do test if the Quantz key helps and how. The exercise is difficult, take your time, slowly repeat, and make sure you’re actively acquiring a new skill with your ear memory and with your instrument. The aim is to keep the sensitivity of your ears awake and quickly react to the demands of sudden harmony changes.

When we have got proficiency with the harmonic qualities of notes, let’s have fun with the weird and tricky side. With pairs of enharmonic notes we are in the most challenging of the Quantz territories: if you can, do test if the Quantz key helps and how. The exercise is difficult, take your time, slowly repeat, and make sure you’re actively acquiring a new skill with your ear memory and with your instrument. The aim is to keep the sensitivity of your ears awake and quickly react to the demands of sudden harmony changes.

Apply newly learned skill to real music situations, starting with simple Adagio or Arioso pieces. Don’t rush. Add dimension and taste how your flute sounds in ensemble playing in a genuine Quantz 9-commas flute temperament.

In unequal temperaments, each key sounds normally with a different degree of stability, which in music translates into an alternation of consonance and dissonances grades, in speeches made of tension and relaxation waves. In the context of Baroque music, this alternation directly relates to the affective content of the music. In Quantz time this is valid for pure instrumental music too, not only for vocal one, where the expression is conveyed by a text. At the time, this was generally understood by composers and performers and perceived in the same way by the listener, especially if cultivated in good taste. And here's where our master Quantz comes back to guide us....

For traverso players, the priority extends beyond mere technical mechanics; it is crucial to revive and maintain the 'harmonic-timbral-affective' aspects in our interpretation of the repertoire, akin to the approach of skilled singers. As Quantz teaches, pitch-intonation-timbre combination is one of the tools to achieve a cantabile, singing-like expression on the flute.

In unequal temperaments, each key sounds normally with a different degree of stability, which in music translates into an alternation of consonance and dissonances grades, in speeches made of tension and relaxation waves. In the context of Baroque music, this alternation directly relates to the affective content of the music. In Quantz time this is valid for pure instrumental music too, not only for vocal one, where the expression is conveyed by a text. At the time, this was generally understood by composers and performers and perceived in the same way by the listener, especially if cultivated in good taste. And here's where our master Quantz comes back to guide us....

For traverso players, the priority extends beyond mere technical mechanics; it is crucial to revive and maintain the 'harmonic-timbral-affective' aspects in our interpretation of the repertoire, akin to the approach of skilled singers. As Quantz teaches, pitch-intonation-timbre combination is one of the tools to achieve a cantabile, singing-like expression on the flute.

In a following article we’ll see how to improve our musical eloquency with the articulation and ornamentation recommendations found in the Versuch.