|

Many of us first encountered Quantz through a teacher or a rehearsal colleague's advice. The notion of a being named "Quantz" exerting an ancestral authority over our sound, embouchure, or tonguing, as well as over our revered masters and virtuosos, began to embed itself in us as a moral duty closely linked to our passion for the traverso. In this series of articles, I'll try to offer a detailed fresh presentation of the author and his book, advice on its interpretation and practical use, and reading keys to make the study more fruitful and organized.

|

My entry into the realm of Quantz was also a day marked by humiliation. During a chamber audition rehearsal, the harpsichordist criticized my execution of certain pickup notes in a Telemann piece. Sides were taken: the violinist rushed to defend me by playing my part, the viola da gamba player nodded and shook his head while intensely watching his bow, and the theorbo player diplomatically slid his frets on the neck. Then, the harpsichordist abruptly stood up, fetched a hefty book titled "On Playing the Flute" from the shelf, its cover as cheerful as a Beatles album cover, and challenged me with a phrase, uttered with sibilant cruelty: "Quantz-Says-That!"

Knowing how to play a decently tuned prelude by Hotteterre in F major or G minor was of little use if a harpsichordist my age had already bothered to read and underline a book (… about flute, wow!) I had only heard of. The next day, I called my bookshop and ordered the book, despite my rudimentary English.

For years, that book wandered through my house, opened to one page or another, duly underlined alongside my notebook. I photocopied the fingering chart and hung it near my music stand, noting it depicted a flute with two keys instead of one...

Knowing how to play a decently tuned prelude by Hotteterre in F major or G minor was of little use if a harpsichordist my age had already bothered to read and underline a book (… about flute, wow!) I had only heard of. The next day, I called my bookshop and ordered the book, despite my rudimentary English.

For years, that book wandered through my house, opened to one page or another, duly underlined alongside my notebook. I photocopied the fingering chart and hung it near my music stand, noting it depicted a flute with two keys instead of one...

|

The traverso reemerged only around the 1960s on stages. Many early performers exploring this new instrument were already established recorder virtuosos, as the recorder had a long history in musical practice, with methods, teachers, and a developed technique, not to mention a contemporary repertoire alongside the historical one from the 17th and 18th centuries. Recordings by legends like Frans Brüggen and Hans-Martin Linde sparked interest in the traverso, its repertoire, and its sources.

Until then, Johann Joachim Quantz was little known as a Baroque era's flute virtuoso, his fame closely tied to his role as flute teacher to Frederick the Great of Prussia, for whom he wrote a vast yet largely unknown body of sonatas and concertos. And that he had also published a weighty treatise on an obsolete sort of flute.

Until then, Johann Joachim Quantz was little known as a Baroque era's flute virtuoso, his fame closely tied to his role as flute teacher to Frederick the Great of Prussia, for whom he wrote a vast yet largely unknown body of sonatas and concertos. And that he had also published a weighty treatise on an obsolete sort of flute.

|

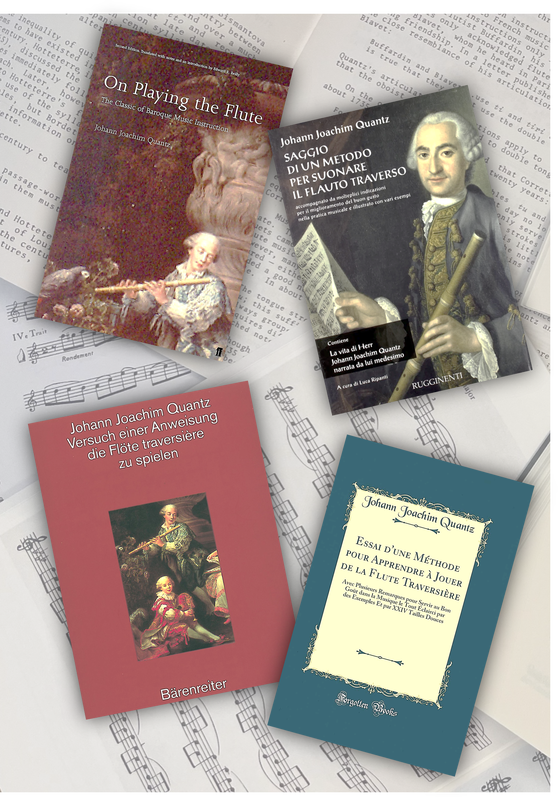

The modern rediscovery of Quantz was notably advanced by the American musicologist Edward R. Reilly (1929-2004). After dedicating his doctoral studies to Quantz, Reilly published the first English translation of the "Versuch" under the title "On Playing the Flute" in 1966, which became a commercial success and a key source for baroque music interpretation.

Reilly's introduction offered a profound revision of Quantz's traditional biography and provided interpretative keys to the text and its application areas. Despite its title, the book is not just about flute playing; it's an extensive analytical essay on musical interpretation, covering a wide range of topics including musical motivation, teaching, taste development, style formation, accompaniment, forms and composition, improvisation, and ornamentation, among others. Today many of us can feel disconcerted with the depth and density of the book, especially regarding technical aspects like tongue strokes or articulation. Quantz's distinction between "arbitrary" Italian ornaments and "essential" French ones might leave some pondering over mysterious culinary traditions. It's comforting to know that many aspects of the book also seemed odd to its contemporary readers... |

The traverso you love to play is not just a seductive musical instrument to blow in but also a gateway to a fascinating journey through the musical world of the past, with Quantz's book serving as one of the most detailed and clear photographs possible. But Quantz's "Versuch" is not the Bible, though it might resemble it in size and density. Nor is it a flute method, although it contains many useful elements for our study. Understanding Quantz is not just about magically making the traverso sound better (but it can save one from humiliations like the one described above). It's advisable to get acquainted with it gradually, just as with other sources for your instrument, such as Hotteterre, Corrette, Mahaut, and others from different domains.

|

Who was Quantz when he published the "Versuch"? Let's first situate ourselves in time and place... Quantz published the book in 1752 in Berlin, simultaneously in German and French, respectively titled "Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen" and "Essai d'une Méthode pour apprendre à jouer de la Flûte traversière." Both books carry a conspicuous dedication to Frederick the Great, indicating not only his patron but likely the inspiration and encouragement for its publication. Frederick, a lover of enlightened French culture, spoke and wrote in French, which was considered a lingua franca among the European aristocracy and diplomacy at the time. This publishing circumstance was exceptional for the period and was motivated by the desire to normalize musical terminology internationally. The presence of many Italian terms, often Germanized, is also significant. From a purely terminological perspective, the "Versuch" is a precious example of the evolution of musical language in an era of change.

|

|

Quantz was not just another member of the royal musical chapel: he had a lifelong salary of 2000 thalers (the same amount paid to Kapellmeister Carl Heinrich Graun) and was exempt from playing in the opera. |

|

Frederick's obsessive fondness for the flute is well-documented. Every evening, he gathered with a select group of musicians to play in private, a repertoire consisting almost entirely of sonatas and concertos, mostly by Quantz. In a small string orchestra, virtuosos like the Benda brothers, Johann Gottlieb Graun, the theorbo player Ernst Gottlieb Baron, and none other than Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach at the harpsichord, succeeded one another over time. Charles Burney was one of the few eyewitnesses to what can be considered one of the most unusual rituals recorded in the history of secular music. The concerts were played in the order of a numbered list that eventually reached 300 titles: at the end of the list, they started again from the first. This ritual remained unchanged from Frederick's years in Rheinsberg until almost the end of his life. Besides providing music, Quantz was the person responsible for setting the tempo of the performance and the only court member authorized to utter a "bravo" at the end of the performance.

|

This was Quantz's status at the time he wrote and published the "Versuch." The privileges Frederick granted him likely also enabled him to encapsulate all the wisdom he had acquired throughout his career in a book. Indeed, as Reilly well evidenced, many of his ideas are the result of deep reflection on his own musical experience.

To understand where this authority came from, we need to go back in time and move further south, towards Saxony and Dresden...

To understand where this authority came from, we need to go back in time and move further south, towards Saxony and Dresden...

© Agostino Cirillo 2024